What is Pyoderma?

Pyoderma, a bacterial skin infection, is a common skin problem, but it is uncommon for pets to develop pyoderma without an underlying cause. It is important to remember that all animals live with organisms on our skin. When a problem, such as an allergy, affects the skin barrier and/or the immune system, the skin becomes more susceptible to invasion by these organisms. Typically, when discussing superficial skin infections, the primary bacteria is Staphylococcus. There are many different types of Staphylococcus bacteria, but only a few are problematic.

What does pyoderma look like?

Pyoderma can have many different presentations. In most pets, there is usually some involvement of the hair follicle. Common lesions include pustules (small bumps filled with pus), papules (red bumps), crusts (scabs), or epidermal collarettes (hairless area of skin with thin rim of dried crust at the edge). There is often associated hair loss (sometimes moth-eaten appearance), redness, and itchiness. Depending on the underlying cause, pyoderma can affect different areas of the body.

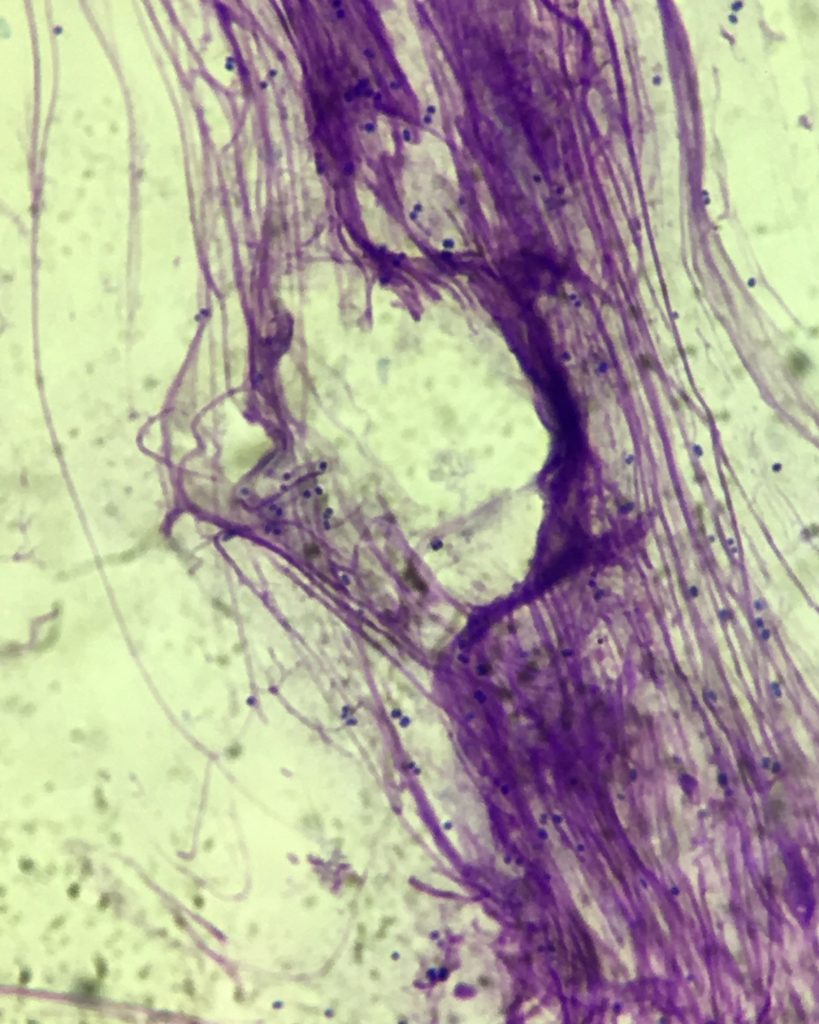

How do we diagnose pyoderma?

We suspect pyoderma clinically based on the history, symptoms, and appearance of the skin, but cytology (looking at slides under the microscope) is very important to confirm presence of cocci (round bacteria which fit the shape of Staphylococcus). Other diseases and problems can look similar to pyoderma, so cytology is used to more definitively determine the problem. Cytology can also be helpful to gauge improvements or changes at recheck appointments.

How do we treat pyoderma?

Treatment often depends on extent, severity, and duration of infection along with associated discomfort for the individual patient. We also consider concurrent diseases or medications before deciding on treatment. In general, topical medications and/or systemic antibiotics may be used. Topical medications can include shampoos, sprays, mousses, etc. that contain an antibiotic or an ingredient that has antimicrobial activity. A couple of examples are chlorhexidine and dilute bleach. Some of these are prescription, while others are over-the-counter. We usually give systemic antibiotics orally; and there are few injectable options available.

For most superficial infections that require systemic antibiotics, the current rule-of-thumb is to treat for a minimum of 3 weeks, with 1 week beyond clinical resolution (i.e. there are no further lesions visible on the patient). Sometimes we need to extend treatment beyond 3-4 weeks, so a recheck appointment PRIOR to finishing the antibiotic is important.

Three weeks might seem like a long time to be on medication, but that length of treatment is based on the skin biology. The skin is constantly regenerating, shedding the old top layer as new cells are made underneath to constantly replenish the skin surface. The normal skin turnover time for a dog is approximately 22 days, so treatment is ideally for one full cycle of skin turnover.

Some patients with recurrent infections may need long-term topical maintenance therapy, but it is also important to treat the underlying disease that is causing the secondary infection.

When is a culture indicated?

A culture is a diagnostic test where a sample of the infection (ex. swab, piece of tissue) is submitted to: a) find out what bacteria are present and b) what those particular bacteria are susceptible to in terms of systemic antibiotics. This can often take 5-7 days for results.

A culture is important for severe/unusual infections, recurrent/chronic infections, or infections that are not responding to treatment as expected. Because culture is the most sensitive way to pick up bacteria, we may recommend it to rule out infection even if there are only a few bacteria present on the skin surface. When submitting a culture, it is always valuable for your veterinarian to have concurrent cytology to best interpret results.

What is methicillin resistance?

Based on culture, your veterinarian may discuss resistance to a particular antibiotic (methicillin). If Staphylococcus is resistant to methicillin, then this can complicate treatment by limiting antibiotic choices, leaving options that may have more side effects and monitoring requirements.

In humans, the most common type of skin bacteria resulting in infection is Staphylococcus aureus, so when there is methicillin resistance, it is called methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). MRSA is certainly a major health concern (www.wormsandgermsblog.com/files/2008/04/M2-MRSA-Owner.pdf), but fortunately, it is a relatively rare problem in pets.

In dogs and cats, the more common infection type is Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, so when there is methicillin resistance, it is called methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP). While MRSP can still be a challenge to treat for the individual patient (www.wormsandgermsblog.com/files/2008/04/JSW-MA3-MRSP-Owner.pdf), it is less of a concern to surrounding healthy humans and pets. Management and follow-up with your veterinarian remains important.

If you think your pet might have pyoderma or any allergic skin disease, we suggest making an appointment with your veterinarian and/or a veterinary dermatologist.

Friendship Dermatology Specialists, led by Dr. Darcie Kunder and Dr. Fiona Lee, is the only board-certified veterinary dermatology group in the District. Specially trained to treat a wide variety of conditions affecting the skin, hair and nails, Friendship Dermatology Specialists see appointments Monday through Friday.

Friendship Dermatology Specialists, led by Dr. Darcie Kunder and Dr. Fiona Lee, is the only board-certified veterinary dermatology group in the District. Specially trained to treat a wide variety of conditions affecting the skin, hair and nails, Friendship Dermatology Specialists see appointments Monday through Friday.

*Featured image courtesy of PetMD.